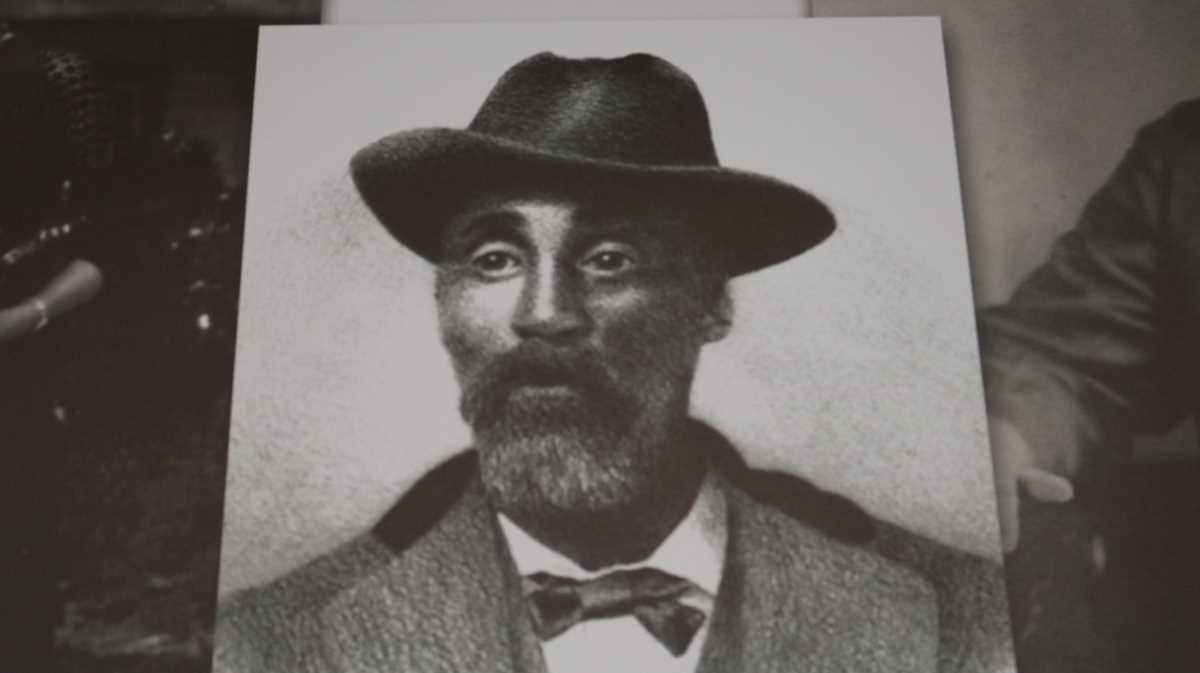

A former Knoxville slave made rags-to-riches history in the early 1900s, becoming Knoxville’s first African-American millionaire.

Caldonia “Cal” Fackler Johnson was born a slave on Oct. 14, 1844, in Knoxville’s Farragut Hotel. Both of Cal Johnson’s parents were born slaves, belonging to the McClung family at Campbell Station.

Robert J. Booker, an African-American historian and founder of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, has researched and published articles on Cal Johnson’s life.

Booker’s research indicates that Johnson’s mother, Harriet McClung Johnson, learned to read and write, as evidenced by the handwritten items in her Bible. She owned and operated a “hotel/restaurant/grocery” store on Willow Street in Knoxville.

Cal Johnson seemed to have inherited a love of horses from his father, Cupid Johnson. Booker says that Cal Johnson’s father was a slave who trained horses and was a winning jockey in the Knoxville area during the mid-1800s. He died, at the age of 49, when Cal was only 14 years old.

So how and when did a former 19th century slave begin amassing his fortune?

Freed from slavery at the age of 21, Cal Johnson started out on the bottom rung of Knoxville's economic ladder. He was awarded a federal contract to take on the grisly task of digging up the bodies of Civil War soldiers who had been buried in temporary graves. He reburied them in the national cemetery or in private cemeteries.

Johnson used the money he earned from these re-interments to open a racetrack and saloons in downtown Knoxville.

Now known as Speedway Circle, the oval stretch of asphalt and surrounding houses in Burlington was once the site of a Cal Johnson racetrack.

The first airplane to travel to Knoxville is said to have landed on Cal Johnson's Burlington racetrack on April 13, 1911. Courtesy of the Beck Cultural Exchange Center.

Johnson opened his first saloon in 1879 on the corner of Gay Street and Wall Avenue. That same year, he ran unsuccessfully for the 5th Ward seat on the Board of Aldermen. But he ran again in 1883 and 1884, winning both times.

Johnson opened his first saloon in 1879 on the corner of Gay Street and Wall Avenue. That same year, he ran unsuccessfully for the 5th Ward seat on the Board of Aldermen. But he ran again in 1883 and 1884, winning both times.

Booker’s research indicates that Cal Johnson donated a house at Vine and Patton streets that was used to open the first African-American YMCA in Knoxville. The donation was made in honor of Johnson’s late wife, Alice, in 1906. Interestingly, when President Theodore Roosevelt dedicated an African-American YMCA in Washington, D.C., in 1908, he praised Cal Johnson for his contributions.

The Johnson business empire took a hit in the early 1900s, when the state of Tennessee outlawed both whiskey and horse racing. Many of Cal Johnson’s businesses were forced to close, although he still had various investments in real estate.

Over the past century, Knoxville’s downtown was remade repeatedly, and the last Cal Johnson-owned building still standing today is a three-story warehouse, constructed in 1898, at 301 State Street. The building housed several Knoxville businesses, including Beeler & Suttle Clothing Manufacturers and later Deaver Dry Good Co.

Knoxville Mayor Madeline Rogero and City Council have taken steps to assure the warehouse, built in the Vernacular Commercial style, will be around for many years to come. The Mayor in December 2015 applied for H-1 protection for the brick warehouse, and the Council last summer voted to apply the overlay protection. An H-1 designation protects a historic structure by requiring review by the Historic Zoning Commission before any permit may be granted for demolition or a significant change to the structure.

“This is one of just a few buildings still standing that reflect the major contributions by African-Americans to the city’s culture and character in the late 1800s and early 1900s,” Mayor Rogero said at the time. “It’s a rare treasure deserving to be safeguarded.”

Knoxville has recognized Johnson’s legacy in other ways. In 1922, the City established Cal Johnson Park, at what is now 507 Hall of Fame Drive; 35 years later, the Cal Johnson Recreation Center was built in the park.

But it’s always been Johnson’s rise from slavery to build a fortune as a self-made entrepreneur and business leader that has fascinated historians.

So … how much money did Cal Johnson earn in his lifetime?

By the time he died in 1925, Johnson was certainly one of the richest men in Tennessee.

“In the early 1880s, he was worth $75,000, and in just a few years, he doubled that amount of money,” Booker said.

Three years before Cal Johnson’s death, the park carrying his name was established. It was to serve African-American families. The park was dedicated on Sept. 21, 1922, with a crowd of 12,000 people in attendance, Booker said. Johnson himself donated more than $1,250 for amenities that included a water fountain, a flagpole, lights and sidewalks in the park.

Booker says it is important to discuss the achievements of Knoxville's African-American community leaders and innovators. That way, he said, “we can all be viewed as equal partners in the community.”

-Communications intern Beverly Banks